This section includes an introduction to the early (pre war) development of gospel music with regard to various types of Media:

Broadcasting

From the 1930s through the 1960s, performances of gospel music were held primarily at religious events in churches and in public venues for African American audiences. During this time, media exposure ranged from fifteen- and twenty- minute broadcasts on radio to one to three hours of daily programs on Black-formatted radio stations. Over the last two decades, gospel music experienced an explosion on many levels. Its audiences have become multiracial in composition. It is broadcast on full-time gospel-formatted stations and on religious television programmes. Its performers are featured in music festivals, with symphony orchestras, and on recordings of popular music; major concerts are jointly sponsored by record companies and national advertisers. Additionally, gospel recordings, once available only in African American “mom and pop” record shops and at performance sites, are now found in mainstream retail outlets.

Source: ‘We’ll Understand It Better By and By”, edited by Bernice Johnson Reagon, Published by Smithsonian Institution Press

__________________________________________________________________

Cinema

“As a particularly visual musical form, gospel music has intrigued filmmakers since the early days or cinema, but successful films featuring spirituals, black gospel, or Southern gospel music have been few and far between”.

Spirituals and Black Gospel

Unfortunately, because both genres have always been composed of predominantly African American audiences and artists white filmmakers have generally avoided the topic. As for the flourishing black cinema of the 1930s to 1950s—the obvious home for African American religious music—only a small percentage of the known titles have survived. Among those that do, The Blood of Jesus (1941) contains numerous renditions of spirituals by The Heavenly Choir, including “Go Down Moses” and “Steal Away to Jesus”. Also featuring spirituals and gospel music are Going to Glory, Come to Jesus (1947), Sunday Sinners (1940), and the short film Broken Earth (1939).

Still, some early Hollywood films do include at least some religious music, including King Vidor’s Hallelujah! (1929), The Song of Freedom (1936), The Green Pastures (1936), and the famed Cabin in the Sky (1943). Director Vincente Minnelli’s first film The Green Pastures and several other early films feature music by the Hall Johnson Choir. The jubilee-singing Golden Gate Quartet have featured performances in Star-Spangled Rhythm (1943), Hollywood Canteen (1944), and A Song Is Born (1948).

Southern Gospel

Southern gospel has been the subject of even fewer films” [with none pre-war].

Source: Encyclopedia of Gospel Music (W.K. McNeil)

__________________________________________________________________

Publications & Periodicals

Key publications and periodicals in order of publication.

1640 – “Bay Psalm Book”

The first US book, that is still in existence, printed in British North America. The book is a ‘metrical Psalter’ (a type of bible translation), first printed in 1640 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Psalms in it are metrical translations into English. The translations are not particularly polished, and not one has remained in use, although some of the tunes to which they were sung have survived (for instance, “Old 100th”). However, its production, just 20 years after the Pilgrims’ arrival at Plymouth, Massachusetts, represents a considerable achievement. It went through several editions and remained in use for well over a century. One of eleven known surviving copies of the first edition sold at auction in November 2013 for $14.2 million, a record for a printed book. The 9th edition was the first edition to contain music – 13 tunes from John Playford’s ‘A Breefe Introduction to the Skill of Musick’ (London, 1654).

1707 – “Hymns and Spiritual Songs”

“Hymns and Spiritual Songs” by Isaac Watts, published in England in 1707, comprised a collection of 210 of his hymns (he wrote almost 600 in all).

1801 – “Collection of Spiritual Songs and Hymns”

Rev. Richard Allen organised the first congregation of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (the AME Church) and because he knew and appreciated the importance of music to his people, one of his first acts as AME minister was to publish a hymnal for the specific use of his congregation. The hymnal contained hymns that had a special appeal to members of his congregation, hymns that were long-time favourites of black Americans. Thus the hymnal provides hymns that represent the black worshipers’ own choices, not the choices of white missionaries and ministers. The hymnal is apparently the earliest source in history that includes hymns to which ‘wandering’ choruses or refrains are attached, that is, choruses that are freely added to any hymn rather than affixed permanently to specific hymns. In 1801 two editions of the collection of hymns were published, the first entitled “A Collection of Spiritual Songs and Hymns Selected From Various Authors by Richard Allen, African Minister”, printed by John Ormrod, who had the previous year printed ‘The Articles of Association of The AME Church of The City Of Philadelphia’ for him. The second was entitled “A Collection of Spiritual Songs and Hymns Selected From Various Authors by Richard Allen, African Minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church”, printed by T. L. Plowman. The first collection consisted of 54 hymn texts, without tunes, drawn mainly from the collections of Dr. Watts, the Wesleys, and other hymn writers favoured by the Methodists, but also including hymns popular with the Baptists. Ten more hymns were added in the second edition.

1844 – “Sacred Harp Songbook”

“The Sacred Harp” is the best-known ‘shape-note’ songbook. It was published in 1844 in Georgia, USA by B. F. White (1800-1879) and E. J. King (ca. 1821-44). This tune book, both the original version and its revisions, has helped promote the style of unaccompanied singing known as “Sacred Harp,” “shape-note,” or “fasola” singing.

“The Sacred Harp” uses notation developed by the progressive New England singing masters William Little and William Smith, who published the “Easy Instructor” in 1801. Their shape-note system was designed to teach sight-reading and enable users to sing complex, sophisticated music.

See also ‘Sacred Harp Singing’ article – Click here

1867 – “Slave Songs of the United States”

“Slave Songs of the United States” was a collection of African American music consisting of 136 songs. Published in 1867, it was the first, and most influential, collection of spirituals to be published. The collectors of the songs were abolitionists William Francis Allen, Lucy McKim Garrison, and Charles Pickard Ware. It is a “milestone not just in African American music but in modern folk history”. It is also the first published collection of African-American music of any kind.

1874 – “Gospel Songs”

In 1874 Philip Paul Bliss edited a revival song-book titled “Gospel Songs” for use in evangelical campaigns, including 50 of his own compositions. In 1875, in conjunction with Ira David Sankey, he compiled “Gospel Hymns and Sacred Songs” and in 1876 he compiled the book known as “Gospel Hymns No. 2”

1903 – “The Souls of Black Folk”

“The Souls of Black Folk” by W. E. B. DuBois published in 1903 contained a series of essays previously published in magazines and journals. Part social documentary, part history, part autobiography, part anthropological field report, a founding work in the literature of black protest, it was an immediate success and remains unparalleled in its scope. The final chapter The Sorrow Songs was the first significant interpretation of the slave spirituals which set the stage for other serious study and comment. Spirituals are, for Du Bois, where the souls of black folk past and present are found.

1916 – “Jubilee Songs of The United States”

“Jubilee Songs of The United States” by Henry Burleigh, published in 1916, was the first publication of a collection of solo arrangements of spirituals. It comprised some 200 ‘folk traditions of his slave ancestors’ arranged as African-American melodies for piano and voice.

1916 – “New Songs of Paradise”

“New Songs of Paradise” by Charles Albert Tindley, published in 1916, was the first publication of a collection of gospel hymns written by a black songwriter (Tindley). A series of six editions were subsequently published with edition No. 6 in 1941 being the first collection to bring together all 46 of Tindley’s published hymns.

1921 – “Gospel Pearls”

“Gospel Pearls” edited by Mrs. Willa A. Townsend, published in 1921 by Sunday School Publishing Board, National Baptist Convention of America, Nashville, TN, was a hymnal containing 163 hymns. Compiled for ‘special use in Sunday Schools, churches, evangelical meetings, conventions and all religious services’, it comprised spirituals, early church music and traditional gospel

__________________________________________________________________

Publishers

E. O. Excell

Edwin Othello Excell (December 13, 1851 – June 10, 1921), commonly known as E. O. Excell, was a prominent American publisher, composer, song leader, and singer of music for church, Sunday school, and evangelistic meetings during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Some of the significant collaborators in his vocal and publishing work included Sam P. Jones, William E. Biederwolf, Gipsy Smith, Charles Reign Scoville, J. Wilbur Chapman, W. E. M. Hackleman, Charles H. Gabriel and D. B. Towner.

Edwin Othello Excell (December 13, 1851 – June 10, 1921), commonly known as E. O. Excell, was a prominent American publisher, composer, song leader, and singer of music for church, Sunday school, and evangelistic meetings during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Some of the significant collaborators in his vocal and publishing work included Sam P. Jones, William E. Biederwolf, Gipsy Smith, Charles Reign Scoville, J. Wilbur Chapman, W. E. M. Hackleman, Charles H. Gabriel and D. B. Towner.

His 1909 stanza selection and arrangement of Amazing Grace became the most widely used and familiar setting of that hymn by the second half of the twentieth century. The influence of his sacred music on American popular culture through revival meetings, religious conventions, circuit chautauquas, and church hymnals was substantial enough by the 1920s to garner a satirical reference by Sinclair Lewis in the novel Elmer Gantry.

Excell compiled or contributed to about ninety secular and sacred song books and is estimated to have written, composed, or arranged more than two thousand of the songs he published. The music publishing business he started in 1881 and that eventually bore his name was the highest volume producer of hymnbooks in America at the time of his death.

Excell was the son of German Reformed minister and self-published author J. J. Excell. He was born in Uniontown, Stark County, Ohio and attended public schools in Ohio and Pennsylvania. After marrying in 1871 near Brady’s Bend, Pennsylvania, he relocated to that state and supported his family for several years as a plasterer, bricklayer, and singing instructor. His focus was turned to sacred music through his experience leading songs at revivals and worship services of Methodist Episcopal churches, first in East Brady and then, starting in 1881, Oil City, Pennsylvania. Between 1877 and 1883 he studied music formally at the Normal Musical Institutes of George F. Root where he also received vocal training under Root’s son, Frederick. He moved to Chicago, base of Root’s operations, in 1883 to pursue music publishing in earnest.

Excell was described as “a big, robust six-footer, with a six-in caliber voice”[9] and extraordinary range that enabled him to solo as baritone or tenor. Publisher George H. Doran observed him leading songs at a revival and later noted that Excell “was a master of mass control; he might easily have become conductor of some mighty chorus”. These talents fostered his early success as a rural singing teacher in Pennsylvania and helped secure a position as church choirmaster for the two years preceding his move to Illinois.

Excell compiled a collection of hymns and gospel songs around 1880 which was published as Sacred Echoes by John J. Hood of Philadelphia in 1881, the year he marked as his start in the business. Sing the Gospel, published around the time of the move to Chicago, was issued under the “E. O. Excell” imprint. Echoes of Eden followed two years later in 1884. An archetype of later “combined” song books was produced in 1885 when contents of Sing the Gospel, Echoes of Eden and limited new material were repackaged into The Gospel in Song, a hymnbook later advertised to contain the songs and solos sung by Excell at Sam Jones’ Gospel meetings.

The working relationship initiated with Jones in 1886 proved to be a pattern of the age. A contemporary writer explained that prominent evangelists always “had their leading singers, they were billed on the hoardings of the cities after the manner of theatrical companies — Moody and Sankey; Sam Jones and Excell; Chapman and Alexander; Torrey and Towner; and so on.” The promotional benefit for a sacred music publisher was enormous. Excell’s books were used in Jones’ revivals and the contents revised over time to suit changing preferences and the needs of the campaigns.

Make His Praise Glorious, published in 1900 as the Triumphant Songs series was approaching its end, contained Excell’s initial arrangement of Amazing Grace based upon the tune New Britain. He compiled and published at least another six song books with the E. O. Excell imprint during his final years with Jones. Excell and his song books received significant exposure in the majority of U.S. states and Canadian provinces of his day during the twenty years they worked together.

Only about seven new song books were published by Excell under his own imprint in the years following Jones’ death, though the annual quantity of books sold still managed to more than double during that time. The business changed to involve a greater number of collaborations destined for other publishers and private label printing of denominational hymnals.

The portfolios of copyrights for contemporary songs and plates for classic hymns that Excell accumulated as a publisher and composer also led to printing work on denominational hymnals. He produced the 1909 edition of Spiritual Hymns of Brethren in Christ in which he held copyrights for about one third of the six hundred songs selected by the hymnal committee. Another example was the original edition of Great Songs of the Church which he produced for the Churches of Christ in 1921.

Excell developed approximately fifty song books and contributed to at least another thirty-eight over his forty-year publishing career. By 1914, his company had produced close to 10 million books and was selling them at a rate of nearly a half million per year. Annual output had grown to more than a million books by 1921, though with margins at wholesale levels.

Excell’s only child, William Alonzo, participated in both the musical event and publishing businesses. At least one publication, Chorus Choir Selections (1918), bore the “E. O. Excell & Son” imprint. “E. O. Excell Company” was utilized on publications created after the founder’s death. Excell’s grandson, known as E. O. Excell, Jr, was also engaged in the family publishing business by 1927.

Estimates of the number of songs authored, composed, or arranged by Excell range from two to three thousand. Two that remain well known are his 1909 arrangement of John Newton’s Amazing Grace and the tune he composed for Johnson Oatman’s Count Your Blessings.

Excell fell ill while assisting Gipsy Smith with a revival in Louisville, Kentucky and returned to Chicago to be hospitalized. He died on June 10, 1921. At least five books listing him as a contributor were published posthumously. One of these was The Excell Hymnal published by his company in 1925; it was completed by his long-time collaborators Hamp Sewell and W. E. M. Hackleman as “a fitting climax to its long line of illustrious predecessors”.

Heirs sold the large E. O. Excell Company copyright portfolio to the Hope Publishing Company in 1931 which they combined with their prior acquisition of a former Ira Sankey firm to create the Biglow-Main-Excell Company.

Source: Extract from Wikipedia

Homer Rodeheaver

(October 4, 1880 – December 18, 1955) was an American evangelist, music director, music publisher, composer of gospel songs, and pioneer in the recording of sacred music.

Born in Cinco Hollow in Hocking County, Ohio, he was taken as a child to Jellico in eastern Tennessee and there worked with his father in the lumber mill business. Although he learned the mountain ballads, he preferred Negro spirituals because they emphasized harmony and rhythm and had a “definite religious purpose.” Rodeheaver early learned to play the cornet but switched to trombone while attending Ohio Wesleyan College, where he also served as a cheerleader.

In 1898 he left college to serve in the Fourth Tennessee Band during the Spanish–American War. Around 1904 he joined evangelist W. E. Biederwolf as music director and then served, from 1910 to 1930, in the same role for Billy Sunday, the most popular evangelist of the period.

In the days before electronic amplification, Rodeheaver quickly discovered that his trombone could be heard when his voice or the piano could not. He often led congregational singing with his trombone, switching from playing to directing halfway through the song and then allowing the trombone to hang on his arm at the elbow.

In his prime, Rodeheaver also used his baritone voice to good effect as a soloist and as a participant in ensembles composed of other members of Sunday’s evangelistic team—especially duets with contralto Virginia Asher. During the heyday of the Sunday evangelistic campaigns, Rodeheaver directed the nation’s largest choruses: from a few hundred to as many as two thousand volunteers in Sunday’s various campaigns. To him there was nothing incongruous about having his choirs sing Horatio R. Palmer’s gospel song “Master, the Tempest is Raging”, followed by the Hallelujah Chorus from Handel’s Messiah.

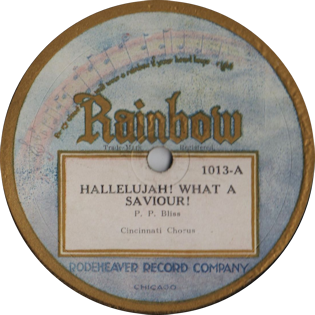

In 1913 Rodeheaver began recording for the Victor Talking Machine Company, a relationship that lasted for twenty years. He also recorded for Gennett, Columbia and for his own Rainbow Records label. Rodeheaver appeared on at least eighteen record labels and five hundred sides during his recording career. His most recorded piece was Sunday’s theme song “Brighten The Corner Where You Are,” which Rodeheaver recorded for at least 17 different labels.

In 1910, Rodeheaver started his own publishing business, the Rodeheaver Company, compiling gospel songs to sell at revivals. In 1936 Rodeheaver purchased the Hall-Mack Company and merged it with his own publishing house, headquartered in Winona Lake, Indiana. Rodeheaver employed songwriters such as B. D. Ackley and Charles H. Gabriel to write songs for his company, but he also composed a number of tunes himself, including most notably, “When Jesus Came.” Around 1922, his company began issuing 78-rpm records on its own Rainbow label, the nation’s first record company devoted solely to gospel music. The Rodeheaver Company was acquired by Word Music in 1969

Source: Extract from Wikipedia

Charlie Tillman

Charles Davis Tillman (March 20, 1861, Tallassee, Alabama – September 2, 1943, Atlanta, Georgia)—also known as Charlie D. Tillman, Charles Tillman, Charlie Tillman, and C. D. Tillman—was a popularizer of the gospel song. He had a knack for adopting material from eclectic sources and flowing it into the mix now known as southern gospel, becoming one of the formative influences on that genre.

Charles Davis Tillman (March 20, 1861, Tallassee, Alabama – September 2, 1943, Atlanta, Georgia)—also known as Charlie D. Tillman, Charles Tillman, Charlie Tillman, and C. D. Tillman—was a popularizer of the gospel song. He had a knack for adopting material from eclectic sources and flowing it into the mix now known as southern gospel, becoming one of the formative influences on that genre.

The youngest son of Baptist preacher James Lafayette Tillman and Mary (Davis) Tillman, for 14 years prior to 1887 he painted houses, sold sheet music for a company in Raleigh, North Carolina, and peddled Wizard Oil. In 1887 he focused his career more on his church and musical talents, singing first tenor in a church male quartet and establishing his own church-related music publishing company in Atlanta.

In 1889 Tillman was assisting his father with a tent meeting in Lexington, South Carolina. The elder Tillman lent the tent to an African American group for a singing meeting on a Sunday afternoon. It was then that young Tillman first heard the spiritual “The Old Time Religion” and then quickly scrawled the words and the rudiments of the tune on a scrap of paper. Tillman published the work to his largely white church market in 1891. Tillman was not first in publishing the song, an honor which goes to G. D. Pike in his 1873 Jubilee Singers and Their Campaign for Twenty Thousand Dollars. Rather, Tillman’s contribution was that he culturally appropriated the song into the repertoire of white southerners, whose music was derived from gospel, a style that was a distinct influence on Buddy Holly and Elvis Presley. As published by Tillman, the song contains verses not found in Pike’s 1873 version. These possibly had accumulated in oral tradition or/and were augmented by lyrics crafted by Tillman. More critically, perhaps, Tillman’s published version of the tune has a more-mnemonic cadence which may have helped it gain wider currency. Tillman’s emendations have characterized the song ever since, in the culture of all southerners irrespective of race. The SATB arrangement in Tillman’s songbooks became known to Alvin York and is thus the background song for the 1941 Academy Award film Sergeant York, which spread “The Old-Time Religion” to audiences far beyond the South. Following Tillman’s nuanced example, editors with a largely white target market such as Elmer Leon Jorgenso formalized the first line as “‘Tis the old-time religion” (likewise the repeated first line of the refrain) to accommodate the song more to the tastes of white southern church congregations and their singing culture.

Tillman was so recognized in his own time that, at the 1893 World Convention of Christian Workers in Boston, he served as songleader in place of Dwight L. Moody’s associate Ira D. Sankey. Tillman’s Assembly Book (1927) was selected by both Georgia and South Carolina for the musical scores used in public school programs. Tillman broke into radio early and performed regularly on Atlanta’s radio station WSB 750 AM. Once in 1930 the NBC radio network put him on the air for an hour featuring his singing while his daughter accompanied on the piano. He also recorded on Columbia Records.

Tillman, who spent most of his life in Georgia and Texas, published 22 songbooks. He is memorialized in the Southern Gospel Museum and Hall of Fame and was among the first individuals to be inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame.

Source: Extract from Wikipedia

__________________________________________________________________

Record Companies

Key record companies publishing early (pre-war) gospel records.

Angelophone Records

Angelophone was an early, short-lived record label from the United States with produced an unusual 7-inch, vertically-cut record. Angelophone discs were produced in a set of 50, featuring a hymn on one side, and a talk about the hymn on the reverse side. The discs usually have a normal paper label on the hymn side, but, similar to early Edison Diamond Discs, have an etched label on the “Hymn Talk” side. Specimens with other paper labels or etched labels on both sides are known. Credited to a firm named “Angelico”, the discs were possibly produced by the Paroquette Record Manufacturing Company. Researches note that both Angelophone Records and Par-o-ket Records were 7-inch, vertically cut discs and that all of the hymn sides were recorded by Henry Burr, a founder of Paroquette. An accompanying hymn book originates from the same year as the records. Angelophone may have been the first disc record label devoted solely to Anglo-American religious music. An earlier gospel company, Sankey Records made by Ira D. Sankey, had produced only cylinders.

Angelophone was an early, short-lived record label from the United States with produced an unusual 7-inch, vertically-cut record. Angelophone discs were produced in a set of 50, featuring a hymn on one side, and a talk about the hymn on the reverse side. The discs usually have a normal paper label on the hymn side, but, similar to early Edison Diamond Discs, have an etched label on the “Hymn Talk” side. Specimens with other paper labels or etched labels on both sides are known. Credited to a firm named “Angelico”, the discs were possibly produced by the Paroquette Record Manufacturing Company. Researches note that both Angelophone Records and Par-o-ket Records were 7-inch, vertically cut discs and that all of the hymn sides were recorded by Henry Burr, a founder of Paroquette. An accompanying hymn book originates from the same year as the records. Angelophone may have been the first disc record label devoted solely to Anglo-American religious music. An earlier gospel company, Sankey Records made by Ira D. Sankey, had produced only cylinders.

Source: Wikipedia

With the success of the Photodrama in mind, and the realisation that records were now highly popular, a few Bible Students set up the Angelico Company in 1916. Ostensibly it was to manufacture and sell phonographs, but with each purchase came a set of 50 Angelophone recordings. For some reason they were numbered 49-98, although it is certain that no 1-48 were ever issued. The records were small seven inch discs using the ‘hill and dale’ method to squeeze two minutes on a side at 85 rpm. They were advertised as ‘Old Fireside Hymns’ sung by the celebrated baritone Henry Burr. On the reverse side (also at 85 rpm) were a series of two minute sermons to explain the hymns. These were uncredited, but were Pastor Russell’s own voice. Those who had questions could write to a ‘Free Information Bureau for Angelophone Patrons’. This of course was the Watch Tower Society.

Source: Watch Tower History

Benson Records

Benson Records was founded by Bob Benson and John T. Benson, beginning as the John T. Benson Music Publishing Company in 1902. The record label started out as Heart Warming Records and would come to house labels such as Impact Records, Greentree Records, RiverSong, StarSong and Home Sweet Home.

Benson Records was founded by Bob Benson and John T. Benson, beginning as the John T. Benson Music Publishing Company in 1902. The record label started out as Heart Warming Records and would come to house labels such as Impact Records, Greentree Records, RiverSong, StarSong and Home Sweet Home.

Heart Warming and their (later – 1965) chief rival Canaan Records (owned by Word Records) were arguably the two biggest and best gospel labels in their time. Producers for the label included Bob Benson (John Benson’s son), Bob MacKenzie and Don Light. Bob MacKenzie in particular produced some of the best gospel albums of that era. Eventually the Benson company dropped the Heart Warming label instead having RiverSong as the southern gospel division and Impact Records and later Benson labels as their contemporary labels.

Source: Wikipedia

Bibletone Records

Bibletone Records was organized in 1942 in New York City by Arthur Becker. The company was the first all-gospel label to release 331⁄3 rpm albums of their releases. It was also one of the first labels to release 10-inch as well as 12-inch long-play albums and one of the first companies to release their singles on 45, as well as 78 rpm.

Bibletone Records was organized in 1942 in New York City by Arthur Becker. The company was the first all-gospel label to release 331⁄3 rpm albums of their releases. It was also one of the first labels to release 10-inch as well as 12-inch long-play albums and one of the first companies to release their singles on 45, as well as 78 rpm.

Initially, the early albums were of choirs, sacred music and children’s music. The company also produced recorded “selected passages of the scriptures [including] Twenty-Third Psalm — Ten Commandments — Sermon on the Mount and others” that were sold at $1.05 each in 1943.

The success of the earliest records of The LeFevres on 78 rpm (in the 1940s), caused the company to shift its focus to Southern Gospel. The company changed ownership several times during the 1950s, operating for a time in Montrose, Pennsylvania and also in Wheaton, Illinois.

The company also produced Christmas albums. One, Merry Christmas Music in 1948, featured the Saintsbury Singers performing a cappella carols with “six sides on 10-inch records.”

Bibletone’s product line in 1948 included three Easter albums — Elijah, The Messiah, and New Hymns of Gladness. In conjunction with those albums, the company advertised its “‘NEW NOISELESS SURFACE’ — a Bibletone recording achievement.”

Bibletone ventured into production of single recordings in 1949. Initially the focus was on “signing of several Southern and Western radio artists.”

The company finally settled in East Orange, New Jersey, under the management of Dick Engel. During Engel’s tenure, the label boasted its own pressing plant, and recorded a number of major Southern gospel groups, including : The LeFevres, The Blue Ridge Quartet, The Rebels Quartet, The Harmoneers, The Homeland Harmony Quartet, The Happy Goodman Family and the Sunshine Boys. Initial releases were often pressed by RCA Custom Pressing but Bibletone became known in the 1950s for their colorful red or blue vinyl records, pressed in the company’s own pressing plant.

Source: Wikipedia

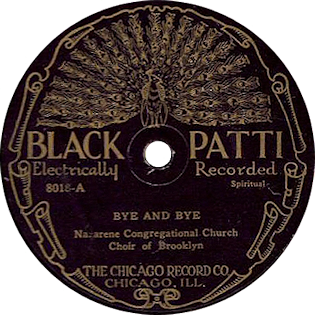

Black Patti Records

Black Patti Records was a short-lived record label in Chicago founded by Mayo Williams in 1927. It was named after the black opera singer Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones, who was called Black Patti because some thought she resembled the Italian opera singer Adelina Patti. The label lasted seven months and produced 55 records. The Black Patti peacock logo was used in the 1960s by Nick Perls for his Belzona and Yazoo labels.

Black Patti Records was a short-lived record label in Chicago founded by Mayo Williams in 1927. It was named after the black opera singer Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones, who was called Black Patti because some thought she resembled the Italian opera singer Adelina Patti. The label lasted seven months and produced 55 records. The Black Patti peacock logo was used in the 1960s by Nick Perls for his Belzona and Yazoo labels.

At Paramount, Mayo Williams was a successful producer of race records, i.e., records made by black musicians to be sold to black customers. When he left Paramount to start Black Patti, he had no equipment, only his Chicago office. The records were pressed at Gennett Records in Richmond, Indiana. The catalog included jazz, blues, sermons, spirituals, and vaudeville skits, most but not all by black entertainers. Willie Hightower was among the musicians who recorded for the label. Williams closed the label before the end of 1927.

Souce: Wikipedia

Brunswick Records

Brunswick Records was founded in 1916. Records under the Brunswick label were first produced by the Brunswick-Balke-Collender Company, a company based in Dubuque, Iowa which had been manufacturing products ranging from pianos to sporting equipment since 1845. The company first began producing phonographs in 1916, then began marketing their own line of records as an after-thought. These first Brunswick records used the vertical cut system like Edison Disc Records, and were not sold in large numbers. They were recorded in the US but sold only in Canada.

In January 1920, a new line of Brunswick Records was introduced in the US and Canada that employed the lateral cut system which was becoming the default cut for 78 discs. Brunswick started its standard popular series at 2000 and ended up in 1940 at 8517. However, when the series reached 4999, they skipped over the previous allocated 5000’s and continued at 6000. Also, when they reached 6999, they continued at 7301 (because the early 7000’s had been previously allocated as their Race series). The parent company marketed them extensively, and within a few years Brunswick became one of the USA’s Big Three record companies, along with Victor and Columbia Records.

In January 1920, a new line of Brunswick Records was introduced in the US and Canada that employed the lateral cut system which was becoming the default cut for 78 discs. Brunswick started its standard popular series at 2000 and ended up in 1940 at 8517. However, when the series reached 4999, they skipped over the previous allocated 5000’s and continued at 6000. Also, when they reached 6999, they continued at 7301 (because the early 7000’s had been previously allocated as their Race series). The parent company marketed them extensively, and within a few years Brunswick became one of the USA’s Big Three record companies, along with Victor and Columbia Records.

The Brunswick line of home phonographs were commercially successful. Brunswick had a hit with their Ultona phonograph capable of playing Edison Disc Records, Pathé disc records, and standard lateral 78s. In late 1924, Brunswick acquired the Vocalion Records label.

Based in Chicago (although they maintained an office and studio in New York), many of the city’s best orchestras and performers recorded for Brunswick. The label’s jazz roster included Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington (usually as the Jungle Band), King Oliver, Johnny Dodds, Andy Kirk, Roger Wolfe Kahn, and Red Nichols. Brunswick initiated a 7000 race series (with the distinctive ‘lightning bolt’ label design, also used for their popular 100 hillbilly series) as well as the Vocalion 1000 race series. These race records series recorded hot jazz, urban and rural blues, and gospel.

When the record industry sales plummeted due to the Great Depression—Warner Bros. leased the Brunswick record operation to Consolidated Film Industries, the parent company of the American Record Corporation (ARC), in December 1931. In 1932, the UK branch of Brunswick was acquired by British Decca. Between early 1932 and 1939, Brunswick was ARC’s flagship label, selling for 75 cents, while all of the other ARC labels were selling for 35 cents.

In 1939, the American Record Corp. was bought by the Columbia Broadcasting System for $750,000, which discontinued the Brunswick label in 1940 in favor of reviving the Columbia label (as well as reviving the OKeh label replacing Vocalion). This, along with the lower than agreed-upon sales/production numbers, violated the Warner lease agreement, resulting in the Brunswick trademark reverting to Warner. In 1941, Warner sold the Brunswick and Vocalion labels to American Decca (which Warner had a financial interest in), with all masters recorded prior to December 1931. Rights to recordings from late December 1931 on were retained by CBS/Columbia.

In 1943, Decca revived the Brunswick label, mostly for reissues of recordings from earlier decades, particularly Bing Crosby’s early hits of 1931 and jazz items from the 1920s. Since then, Decca and its successors have had ownership of the historic Brunswick Records archive from this time period.

Source: Extrat from Wikipedia

Columbia Records

Columbia Records is an American record label founded in 1887, evolving from the American Graphophone Company, the successor to the Volta Graphophone Company. Columbia is the oldest surviving brand name in the recorded sound business, and the second major company to produce records.

The Columbia Phonograph Company was founded in 1887 by stenographer, lawyer and New Jersey native Edward D. Easton (1856–1915) and a group of investors. It derived its name from the District of Columbia, where it was headquartered. At first it had a local monopoly on sales and service of Edison phonographs and phonograph cylinders in Washington, D.C., Maryland, and Delaware. As was the custom of some of the regional phonograph companies, Columbia produced many commercial cylinder recordings of its own, and its catalogue of musical records in 1891 was 10 pages.

Columbia’s ties to Edison and the North American Phonograph Company were severed in 1894 with the North American Phonograph Company’s breakup. Thereafter it sold only records and phonographs of its own manufacture. In 1902, Columbia introduced the “XP” record, a moulded brown wax record, to use up old stock. Columbia had introduced black wax records in 1903. According to one source, they continued to mould brown waxes until 1904 with the highest number being 32601, “Heinie”, which is a duet by Arthur Collins and Byron G. Harlan. The molded brown waxes may have been sold to Sears for distribution (possibly under Sears’ Oxford trademark for Columbia products).

Columbia began selling disc records (invented and patented by Victor Talking Machine Company’s Emile Berliner) and phonographs in addition to the cylinder system in 1901, preceded only by their “Toy Graphophone” of 1899, which used small, vertically cut records. For a decade, Columbia competed with both the Edison Phonograph Company cylinders and the Victor Talking Machine Company disc records as one of the top three names in American recorded sound.

After an abortive attempt in 1904 to manufacture discs with the recording grooves stamped into both sides of each disc—not just one—in 1908 Columbia commenced successful mass production of what they called their “Double-Faced” discs, the 10-inch variety initially selling for 65 cents apiece. The firm also introduced the internal-horn “Grafonola” to compete with the extremely popular “Victrola” sold by the rival Victor Talking Machine Company. During this era, Columbia used the “Magic Notes” logo—a pair of sixteenth notes (semiquavers) in a circle—both in the United States and overseas (where this particular logo would never substantially change).

Columbia stopped recording and manufacturing wax cylinder records in 1908, after arranging to issue celluloid cylinder records made by the Indestructible Record Company of Albany, New York, as “Columbia Indestructible Records”. In July 1912, Columbia decided to concentrate exclusively on disc records and stopped manufacturing cylinder phonographs, although they continued selling Indestructible’s cylinders under the Columbia name for a year or two more.

In late 1922, Columbia went into receivership. The company was bought by its English subsidiary, the Columbia Graphophone Company in 1925 and the label, record numbering system, and recording process changed. On February 25, 1925, Columbia began recording with the electric recording process licensed from Western Electric. “Viva-tonal” records set a benchmark in tone and clarity unequaled on commercial discs during the 78-rpm era. The first electrical recordings were made by Art Gillham, the “Whispering Pianist”. In a secret agreement with Victor, electrical technology was kept secret to avoid hurting sales of acoustic records.

In 1926, Columbia acquired OKeh Records and its growing stable of jazz and blues artists. Columbia had already built a catalog of blues and jazz artists, including Bessie Smith in their 14000-D Race series. Columbia also had a successful “Hillbilly” series (15000-D). In 1928, Paul Whiteman, the nation’s most popular orchestra leader, left Victor to record for Columbia.

Columbia used acoustic recording for “budget label” pop product well into 1929 on the labels Harmony, Velvet Tone (both general purpose labels), and Diva (sold exclusively at W.T. Grant stores). When Edison Records folded, Columbia was the oldest surviving record label.

In 1931, the British Columbia Graphophone Company (itself originally a subsidiary of American Columbia Records, then to become independent, actually went on to purchase its former parent, American Columbia, in late 1929) merged with the Gramophone Company to form Electric & Musical Industries Ltd. (EMI). EMI was forced to sell its American Columbia operations (because of anti-trust concerns) and the Grigsby-Grunow Company, makers of the Majestic Radio were the purchaser. But Majestic soon fell on hard times. An abortive attempt in 1932 (around the same time that Victor was experimenting with its 331⁄3 “program transcriptions”) was the “Longer Playing Record”, a finer-grooved 10″ 78 with 4:30 to 5:00 playing time per side. Columbia issued about eight of these (in the 18000-D series), as well as a short-lived series of double-grooved “Longer Playing Records” on its Clarion Records, Harmony and Velvet Tone labels. All of these experiments (and indeed the Clarion, Harmony and Velvet Tone labels) were discontinued by mid-1932.

A longer-lived marketing ploy was the Columbia “Royal Blue Record,” a brilliant blue laminated product with matching label. Royal Blue issues, made from late 1932 through 1935, are particularly popular with collectors for their rarity and musical interest. The Columbia plant in Oakland, California, did Columbia’s pressings for sale west of the Rockies and continued using the Royal Blue material for these until about mid-1936.

With the Great Depression’s tightened economic stranglehold on the country, in a day when the phonograph itself had become a luxury, nothing slowed Columbia’s decline. It was still producing some of the most remarkable records of the day, especially on sessions produced by John Hammond and financed by EMI for overseas release. Grigsby-Grunow went under in 1934 and was forced to sell Columbia for a mere $70,000 to the American Record Corporation (ARC). This combine already included Brunswick as its premium label so Columbia was relegated to slower sellers. By late 1936, pop releases were discontinued, leaving the label essentially defunct.

As southern gospel developed, Columbia had astutely sought to record the artists associated with the emerging genre; for example, Columbia was the only company to record Charles Davis Tillman. Most fortuitously for Columbia in its Depression Era financial woes, in 1936 the company entered into an exclusive recording contract with the Chuck Wagon Gang, a hugely successful relationship which continued into the 1970s. A signature group of southern gospel, the Chuck Wagon Gang became Columbia’s bestsellers with at least 37 million records, many of them through the aegis of the Mull Singing Convention of the Air sponsored on radio (and later television) by southern gospel broadcaster J. Bazzel Mull (1914–2006).

Another event in this period that would prove to be of importance to Columbia was the 1937 hiring of talent scout, music writer, producer, and impresario John Hammond. Alongside his significance as a discoverer, promoter, and producer of jazz, blues, and folk artists during the swing music era, Hammond had already been of great help to Columbia in 1932–33. Through his involvement in the UK music paper Melody Maker, Hammond had arranged for the struggling US Columbia label to provide recordings for the UK Columbia label, mostly using the specially created Columbia W-265000 matrix series. Hammond would also exert an enormous cultural effect on the emerging rock music scene thanks to his championing of reissue LPs of the music of blues artists Robert Johnson and Bessie Smith.

In 1938 ARC, including the Columbia label in the US, was bought by William S. Paley of the Columbia Broadcasting System for US$750,000. CBS revived the Columbia label in place of Brunswick and the OKeh label in place of Vocalion. CBS renamed the company Columbia Recording Corporation and retained control of all of ARC’s past masters, but in a complicated move, the pre-1931 Brunswick and Vocalion masters, as well as trademarks of Brunswick and Vocalion, reverted to Warner Bros. (which had leased its whole recording operation to ARC in early 1932) and Warners sold it all to Decca Records in 1941.

Source: Extract from Wikipedia

OKeh Records

OKeh Records is an American record label founded by the Otto Heinemann Phonograph Corporation, a phonograph supplier established in 1916, which branched out into phonograph records in 1918. The name was originally spelled “OkeH”, formed from the initials of Otto K. E. Heinemann, but later changed to “OKeh”.

OKeh Records is an American record label founded by the Otto Heinemann Phonograph Corporation, a phonograph supplier established in 1916, which branched out into phonograph records in 1918. The name was originally spelled “OkeH”, formed from the initials of Otto K. E. Heinemann, but later changed to “OKeh”.

Since 1926, Okeh has been a subsidiary of Columbia Records, now itself a subsidiary of Sony Music. Today, Okeh is an imprint of Sony Masterworks, a specialty label of Columbia.

Okeh was founded by Otto K. E. Heinemann, a German-American manager for the U.S. branch of Odeon Records, which was owned by Carl Lindstrom. In 1916, Heinemann incorporated the Otto Heinemann Phonograph Corporation, set up a recording studio and pressing plant in New York City, and started the label in 1918.

The first discs were vertical cut, but later the more common lateral-cut method was used. The label’s parent company was renamed the General Phonograph Corporation, and the name on its record labels was changed to OKeh. The common 10-inch discs retailed for 75 cents each, the 12-inch discs for $1.25. The company’s musical director was Fred Hager, who was also credited under the pseudonym Milo Rega (his middle name and his surname reversed).

Okeh issued popular songs, dance numbers, and vaudeville skits similar to other labels, but Heinemann also wanted to provide music for audiences neglected by the larger record companies.[citation needed] Okeh produced lines of recordings in German, Czech, Polish, Swedish, and Yiddish for immigrant communities in the United States. Some were pressed from masters leased from European labels, while others were recorded by Okeh in New York.

Okeh’s early releases included music by the New Orleans Jazz Band. In 1920, Perry Bradford encouraged Fred Hager, the director of artists and repertoire (A&R), to record blues singer Mamie Smith. The records were popular, and the label issued a series of race records directed by Clarence Williams in New York City and Richard M. Jones in Chicago. From 1921–1932, this series included music by Williams, Lonnie Johnson, King Oliver, and Louis Armstrong. Also recording for the label were Bix Beiderbecke, Bennie Moten, Frankie Trumbauer, and Eddie Lang. As part of the Carl Lindström Company, Okeh’s recordings were distributed by other labels owned by Lindstrom, including Parlophone in the UK.[citation needed]

In 1926, Okeh was sold to Columbia Records. Ownership changed to the American Record Corporation (ARC) in 1934, and the race records series from the 1920s ended. CBS bought the company in 1938. OkeH was a label for rhythm and blues during the 1950s, but jazz albums continued to be released, as in the work of Wild Bill Davis and Red Saunders.

In 1926, Okeh was sold to Columbia Records. Ownership changed to the American Record Corporation (ARC) in 1934, and the race records series from the 1920s ended. CBS bought the company in 1938. OkeH was a label for rhythm and blues during the 1950s, but jazz albums continued to be released, as in the work of Wild Bill Davis and Red Saunders.

General Phonograph Corporation used Mamie Smith’s popular song “Crazy Blues” to cultivate a new market. Portraits of Smith and lists of her records were printed in advertisements in newspapers such as the Chicago Defender, the Atlanta Independent, New York Colored News, and others popular with African-Americans (though Smith’s records were part of Okeh’s regular 4000 series). Okeh had further prominence in the demographic, as African-American musicians Sara Martin, Eva Taylor, Shelton Brooks, Esther Bigeou, and Handy’s Orchestra recorded for the label. Okeh issued the 8000 series for race records. The success of this series led Okeh to start recording music where it was being performed, known as remote recording or location recording. Starting in 1923, Okeh sent mobile recording equipment to tour the country and record performers not heard in New York or Chicago. Regular trips were made once or twice a year to New Orleans, Atlanta, San Antonio, St. Louis, Kansas City, and Detroit.

Source: Extract from Wikipedia

R ainbow Records

ainbow Records

Rainbow Records was a record label based in the United States of America in the 1920s which featured recordings of Christian gospel music, hymns, and spirituals.

Rainbow Records were made by the Rodeheaver Record Company of Chicago, Illinois, which in turn was owned by trombonist and composer Homer Rodeheaver.

Rainbow Records were standard lateral-cut “78” double-sided disc records. The audio fidelity is decidedly below average for the era, and all are acoustically recorded. Some seem to have been recorded and pressed by Gennett Records.

Source: Wikipedia

Sacred Records

Sacred Records was a religious music record label founded in 1944 by Earle E. Williams.

Earle E. Williams, a minister of youth and music director in the Los Angeles area, decided to start a religious music record label in 1944 as a solution to the problem of obtaining the records he needed for his work, which included broadcasting a weekly half-hour radio program every Sunday at noon on local station KXLA. In a 1947 interview, Williams described to United Press International (UPI), “I sold my car, ray dog, my wife’s spinet, a camera and a renovated church organ and borrowed the rest on a note to get the $3,000 I had to have to start production.

Based in Los Angeles, Sacred Records recorded and published religious music. The label merged with Kansas City’s White Church Records in 1949, and by the following year the company had opened new offices in Kansas City, Philadelphia, and New York.

Source: Wikipedia

Supertone Records

Supertone Records was an American record label in the 1920s. Supertone Records were marketed by Sears, Roebuck & Co. in 1924 and again in 1929–1931. The Chicago store Straus & Schram Company produced a separate Supertone series between 1925 and 1928. Supertone was one of several record disc brand names marketed by Sears.

Supertone records were initially made by the Fletcher Record Company in 1924. The discs produced by Fletcher included midwestern dance bands. When Fletcher failed in mid–1924, Bridgeport Die & Machine Company began producing Supertone discs in late 1924.

Sears did not register the Supertone brand name for record production, and after Sears discontinued marketing the records, Straus & Schram used the name, exclusively selling records produced by Regal (Scranton Button Company), Paramount Records, then in Grey Gull in 1925. In 1926, Pathé Records supplied pressings until late 1927–early 1928, when Columbia’s Harmony division started a 1000–S series of Supertone records until mid–1928 when Sears restarted their Supertone series (then Straus & Schram Supertone’s renamed Puritone).

Sears claimed and marketed the brand again in 1928. Between 1928 and through 1930, Gennett pressed Supertone Records using their own masters. When Gennett was discontinued in late 1930, Sears contracted with Brunswick Radio Corporation to produce Supertone Records, which lasted through 1931.

The 1928–1930 Gennett pressed Supertone discs are most commonly seen. The earlier versions, as well as the short-lived Brunswick versions, are quite scarce.

Source: Wikipedia

Victor Records (Victor Talking Machine Company)

The Victor Talking Machine Company was an American record company and phonograph manufacturer headquartered in Camden, New Jersey.

The company was founded by engineer Eldridge R. Johnson, who had previously made gramophones to play Emile Berliner’s disc records. After a series of legal wranglings between Berliner, Johnson and their former business partners, the two joined to form the Consolidated Talking Machine Co. in order to combine the patents for the record with Johnson’s patents improving its fidelity. Victor Talking Machine Co. was incorporated officially in 1901 shortly before agreeing to allow Columbia Records use of its disc record patent.

Victor had acquired the Pan-American rights to use the famous trademark of the fox terrier Nipper listening to a gramophone when Berliner and Johnson affiliated their fledgling companies. The original painting was an oil on canvas by Francis Barraud in 1898. The original painting still shows the contours of the Edison-Bell phonograph beneath the paint of the gramophone when viewed in the correct light.

Before 1925, recording was done by the same purely mechanical, non-electronic “acoustical” method used since the invention of the phonograph nearly fifty years earlier. No microphone was involved and there was no means of amplification. The recording machine was essentially an exposed-horn acoustical record player functioning in reverse. One or more funnel-like metal horns was used to concentrate the energy of the airborne sound waves onto a recording diaphragm, which was a thin glass disc about two inches in diameter held in place by rubber gaskets at its perimeter. The sound-vibrated center of the diaphragm was linked to a cutting stylus that was guided across the surface of a very thick wax disc, engraving a sound-modulated groove into its surface. The wax was too soft to be played back even once without seriously damaging it, although test recordings were sometimes made and sacrificed by playing them back immediately. The wax master disc was sent to a processing plant where it was electroplated to create a negative metal “stamper” used to mold or “press” durable replicas of the recording from heated “biscuits” of a shellac-based compound. Although sound quality was gradually improved by a series of small refinements, the process was inherently insensitive. It could only record sources of sound that were very close to the recording horn or very loud, and even then the high-frequency overtones and sibilants necessary for clear, detailed sound reproduction were too feeble to register above the background noise. Resonances in the recording horns and associated components resulted in a characteristic “horn sound” that immediately identifies an acoustical recording to an experienced modern listener and seemed inseparable from “phonograph music” to contemporary listeners.

From the start, Victor innovated manufacturing processes and soon rose to pre-eminence by recording famous performers. In 1903, it instituted a three-step mother-stamper process to produce more stampers and records than previously possible. After improving the quality of disc records and players, Johnson began an ambitious project to have the most prestigious singers and musicians of the day record for Victor, with exclusive agreements where possible. Even if these artists demanded royalty advances which the company could not hope to make up from the sales of their records, Johnson shrewdly knew that he would get his money’s worth in the long run in promotion of the Victor brand name. These new celebrity recordings bore red labels, and were marketed as Red Seal records. For many years these records were single-sided; only in 1923 did Victor begin offering Red Seals in double-sided form. Countless advertisements were published praising renowned stars of the opera and concert stages and boasting that they recorded only for Victor. As Johnson intended, much of the record-buying public assumed from this that Victor Records must be superior.

In the company’s early years, Victor issued recordings on the Victor, Monarch and De Luxe labels, with the Victor label on 7-inch records, Monarch on 10-inch records and De Luxe on 12-inch records. De Luxe Special 14-inch records were briefly marketed in 1903–1904. In 1905, all labels and sizes were consolidated into the Victor imprint.

The first jazz and blues records were recorded by the Victor Talking Machine Company. The Victor Military Band recorded the first recorded blues song, “The Memphis Blues”, on July 15, 1914 in Camden, New Jersey. In 1917, The Original Dixieland Jazz Band recorded “Livery Stable Blues”, and established jazz as popular music.

The advent of radio as a home entertainment medium in the early 1920s presented Victor and the entire record industry with new challenges. Not only was music becoming available over the air free of charge, but a live broadcast made using a high-quality microphone and heard over a high-quality receiver provided clearer, more “natural” sound than a contemporary record. In 1925, Victor switched from the acoustical or mechanical method of recording to the new microphone-based electrical system developed by Western Electric. Victor called its version of the improved fidelity recording process “Orthophonic”, and sold a new line of record players, called “Orthophonic Victrolas”, scientifically designed to play these improved records. Victor’s first electrical recordings were made and issued in the spring of 1925. However, in order to create sufficient catalogs of them to satisfy anticipated demand, and to allow dealers time to liquidate their stocks of acoustical recordings, Victor and its rival, Columbia, agreed to keep secret from the public, until near the end of 1925, the fact that they were making the new electrical recordings which offered a vast improvement over the ones currently available. Then, with a large advertising campaign, Victor openly announced the new technology and introduced its Orthophonic Victrolas on “Victor Day”, November 2, 1925.

Victor’s first commercial electrical recording was made at the company’s Camden, New Jersey studios on February 26, 1925. A group of eight popular Victor artists, Billy Murray, Frank Banta, Henry Burr, Albert Campbell, Frank Croxton, John Meyer, Monroe Silver, and Rudy Wiedoeft gathered to record “A Miniature Concert”. Several takes were recorded by the old acoustical process, then additional takes were recorded electrically for test purposes. The electrical recordings turned out well, and Victor issued the results that summer as the two sides of 12-inch 78 rpm record Victor 35753.

The origins of country music as we know it today can be traced to two seminal influences and a remarkable coincidence. Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family are considered the founders of country music and their songs were first captured at an historic recording session in Bristol, Tennessee (also known as the Bristol Sessions) on August 1, 1927, where Ralph Peer was the talent scout and recording engineer for Victor.

In 1926, Johnson sold his controlling (but not holding) interest in the Victor Company to the banking firms of JW Seligman and Spyer & Co, who in turn sold Victor to the Radio Corporation of America in 1929. It then became known briefly as the Radio-Victor Division of the Radio Corporation of America, then the RCA Manufacturing Company, the RCA Victor Division and in 1968, RCA Records. Most record labels continued to bear only the “Victor” name until 1946, when the labels changed to “RCA Victor” and eventually, to simply “RCA” in late 1968, “Victor” becoming the label designation for RCA’s popular music releases. (See RCA and RCA Records for later history of the Victor brand name.)

Victor kept meticulous written records of all of its recordings. The files cover the period 1903 to 1958 (thus including the RCA Victor era, as well as the Victor Talking Machine Co. era). These written records are among the most extensive and important sources of available primary discographic information in the world. There were three main categories of files: a daily log of recordings for each day, a file maintained for each important Victor artist, and a 4″x6″ index card file kept in catalog number order. There are about 15,000 daily log pages, each titled “Recording Book,” that are numbered chronologically. Each recording was assigned a “matrix number” to identify the recording. When issued, the recording had a “catalog number,” almost always different from the matrix number, on the record label. As of 2010, the remaining pages available at the Victor archives go only up to April 22, 1935. Victor’s original pages after this date were apparently discarded or lost at some point. However, Victor’s ties with EMI in England, and at Hayes, Hillingdon, in London, EMI has more recent pages. These pages were sent at the time they were first written and therefore do not have the annotations made afterwards. Most, but not all, daily log information for recordings made for synchronization with motion pictures were kept separately, and the separate synchronization recording information is missing from the Victor archives.

Victor also issued annual catalogs of all available recordings with monthly supplements announcing the release of new and forthcoming records issued throughout the year. These publications were carefully prepared and were lavishly illustrated with many photographs and advertisements of popular Victor recording artists.

The Encyclopedic Discography of Victor Recordings (EDVR) is a continuation of a project of Ted Fagan and William Moran to make a complete discography of all Victor recordings. The Victor archive files are a major source of information for this project.

In 2011, the Library of Congress and Victor catalog owner Sony Music Entertainment launched the National Jukebox offering streaming audio of more than 10,000 pre-1925 recorded works. This made the recordings, much of them not widely available since World War I, available for listening by the general public.

In September 1906, Victor introduced a new line of talking machines with the turntable and amplifying horn tucked away inside a wooden cabinet, the horn being completely invisible. This was not done for reasons of audio fidelity, but for visual aesthetics. The intention was to produce a phonograph that looked less like a piece of machinery and more like a piece of furniture. These internal horn machines, trademarked with the name Victrola, were first marketed to the public in September of that year and were an immediate hit. Soon an extensive line of Victrolas was available, ranging from small tabletop models selling for $15, through many sizes and designs of cabinets intended to go with the decor of middle-class homes in the $100 to $250 range, up to $600 Chippendale and Queen Anne-style cabinets of fine wood with gold trim designed to look at home in elegant mansions. Victrolas became by far the most popular type of home phonograph, and sold in great numbers until the end of the 1920s. RCA Victor continued to market record players under the Victrola name until the late 1960s.

Source: Extract from Wikipedia

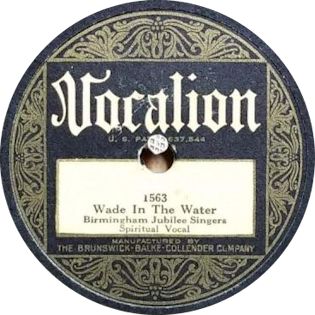

Vocalion Records

Vocalion Records is an American record company and label active for many years in the U.S. and the U.K. Vocalion (pronounced “vo-CAL-yun”) was founded in 1916 by the Aeolian Piano Company of New York City, which introduced a retail line of phonographs at the same time. The name was derived from one of their corporate divisions, the Vocalion Organ Company. The label issued single-sided, vertical-cut disc records but switched to double-sided. In 1920 it switched to the more common lateral-cut system.

In 1925 the label was acquired by Brunswick Records. During the 1920s Vocalion also began the 1000 race series, records recorded by and marketed to African Americans.

In April 1930, Warner Bros. bought Brunswick Records and. In December 1931 Warner Bros. licensed the entire Brunswick and Vocalion operation to the American Record Corporation. ARC used Brunswick as their flagship 75-cent label and Vocalion as one of their 35-cent labels. New signings (Dick Himber, Clarence Williams, Leroy Carr) contributed to the growing popularity of the label.

Starting in about 1935, Vocalion became even more popular with the signing of Billie Holiday, Mildred Bailey, Stuff Smith, Putney Dandridge, and Red Allen. Coupled with other short-term signings, including Fletcher Henderson, Phil Harris, Earl Hines, and Isham Jones, and their healthy Race and Country releases made Vocalion a powerhouse presence.

In 1935, Vocalion started reissuing titles that were still selling from the recently discontinued OKeh label. In 1936 and 1937 Vocalion produced the only recordings by blues guitarist Robert Johnson (as part of their ongoing field recording of blues, gospel and “out of town” jazz groups). From 1935 through 1940, Vocalion was one of the most popular labels for small-group swing, blues, and country. After the short-lived Variety label was discontinued (in late 1937), many titles were reissued on Vocalion, and the label continued to release new recordings made by Master/Variety artists through 1940. This added Cab Calloway and the Duke Ellington small groups-within-his-band (Rex Stewart, Johnny Hodges, Barney Bigard and Cootie Williams) to the label.

ARC was purchased by CBS and Vocalion became a subsidiary of Columbia Records in 1938. The popular Vocalion label was discontinued in 1940. The discontinuance of Vocalion (along with Brunswick in favor of the revived Columbia label) voided the lease arrangement Warner Bros. had made with ARC in late 1931. In a complicated move, Warner Bros. got the two labels back and promptly sold them to Decca, but CBS retained control of the post-1931 Brunswick and Vocalion masters.

The name Vocalion was resurrected in the late 1950s by Decca (US) as a budget label for back-catalog reissues. This incarnation of Vocalion ceased operations in 1973; however, its replacement as MCA’s budget imprint, Coral Records, kept many Vocalion titles in print. In 1975, MCA reissued five albums on the Vocalion label.

In the UK, Decca used the Vocalion label mainly to issue US artists, replacing its Vogue label, the rights to whose name had reverted to the French Disques Vogue.

In 1997 the Vocalion brand was brought back for a new series of compact discs produced by Michael Dutton, of Dutton Laboratories, in Watford, England. This label specializes in sonic refurbishments of recordings made between the 1920s and the 1970s, often leasing master recordings made by Decca and EMI.

Source: Wikipedia

__________________________________________________________________